Highlights from the Grove Design Diary

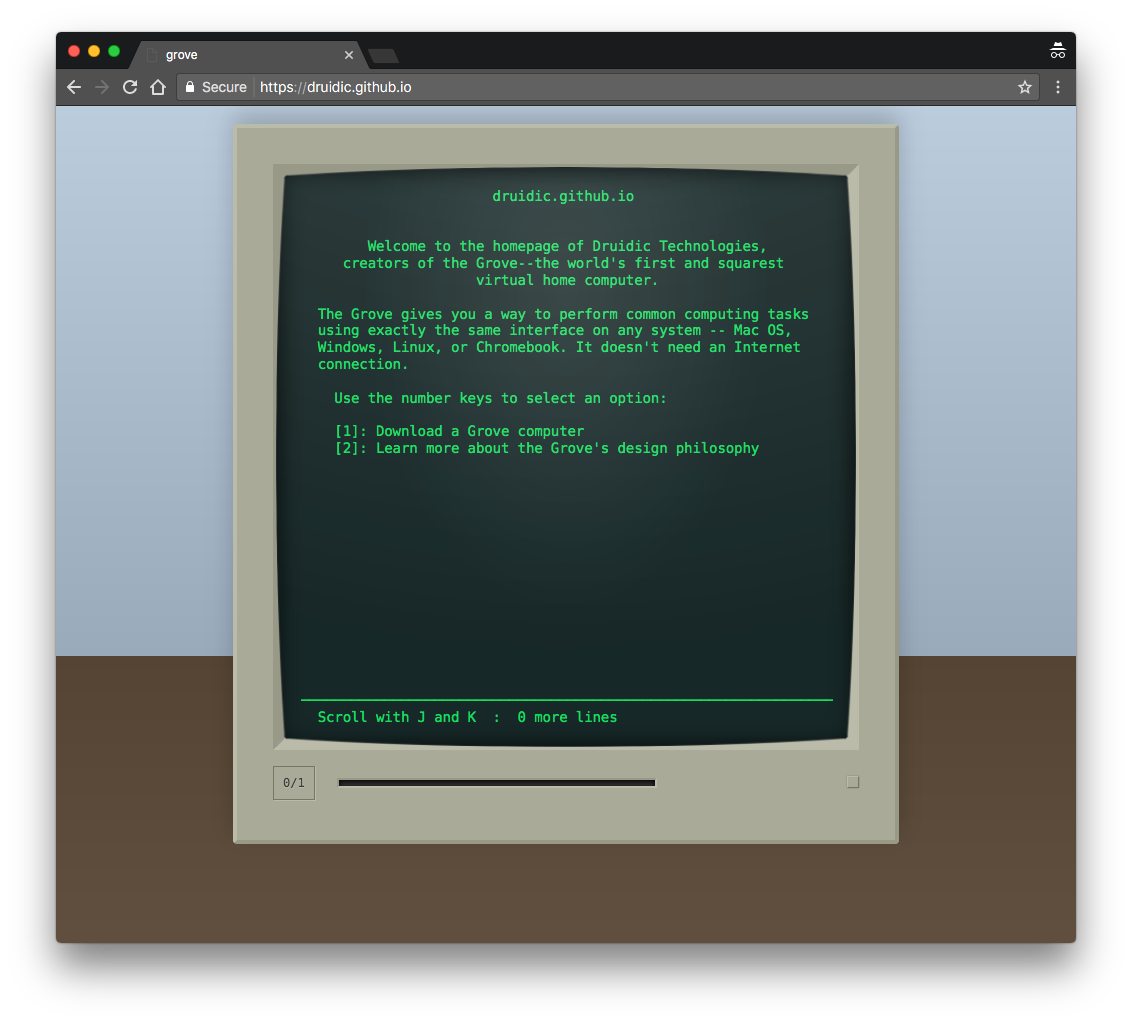

For the last year or so, I’ve been working on a browser-based development environment that I call the Grove (the name hints at a third alternative to Eric Raymond’s cathedral/bazaar binary). The first version was more of a philosophical experiment than anything else. You can play around with it and read more about its goals here.

I’m no longer working on that version, though. It’s been superseded by a new project that aims to achieve the same goals with a slightly less austere interface.

While working on the Grove I kept a design diary. My main reason for doing so was to document my decision-making process so I wouldn’t thrash between solutions as various facets of the problem asserted themselves. Some parts of the diary turned out to be interesting, so I figured they’d make a good blog post.

The text is in a code block because I wrote it using a text editor I wrote for the Grove, which kludgily forced you to hard-wrap every line. Some of the words are hard-hyphenated, so I can’t just reflow the paragraphs without some manual effort. I like the way it looks monospaced, anyway.

Elisions from the original text are marked by [. . .].

Thursday, July 27

[. . .]

On my current project at work, I've grown accustomed to

waiting for long CI builds -- two to four hours, most

of the time. I've realized that such long builds have

effects on the health of the project beyond simple

delays. Long builds lead to frequent task switching,

and necessitate having multiple feature branches running

in git simultaneously. If builds take 4 hours I'm not

going to push straight to develop and risk breaking

everyone else.

The Grove's architecture makes long-running tests

impossible. Jasmine has to jump through hoops to accom-

modate asynchronous code, which can potentially be long-

running. The slow, labyrinthine tests that such code

necessitates are totally impossible to write on a Grove,

since all events are handled by a single main() function

and applications are forced to represent every asynch-

ronous event as a sequence of state transitions.

It remains to be seen if this approach will actually

scale to larger applications. Callback hell may be

replaced by state variable hell, in which the set of

states that must be considered to reason about what a

given async event will do explodes.

Friday, July 28

The whole "Desktop" metaphor of PC UIs is pretty out-

dated, when you think about it, simply because most

desks these days have computers on them and the majority

of the work transacted at the desk actually takes place

in the virtual realm.

Humans created computers because the real world was

complicated and hard to reason about, and computers were

fast(er than humans) and boneheadedly straightforward.

Computers enabled us to create models of the world and

apply them consistently.

I think at some point people stopped seeing that one of

the major virtues of computers was their simplicity. We

now have computer systems that are at least as hard to

understand as the "real" world--if computers can even be

separated from the "real" world anymore. To a large ex-

tent, computers have become our reality.

The result is that we no longer have computers, the way

people in the '80s had computers. Reality is just more

complicated now, and faster, and our tools for making

sense of it and predicting it are constantly outmatched

because they are themselves part of the thing they're

supposed to be modeling.

The Grove is a desktop computer for the modern desk.

Which is to say, it's a literal black box where the only

inputs and outputs are explicit ones. You have a key-

board, a display, and a printer. That's it.

[. . .]

Saturday, July 29

I learned to program in Visual Basic. In VB there's no

project configuration or build setup you have to do.

You just create a "form", drag some UI elements onto it,

write some code to give them behavior, and hit "run".

And it runs.

I don't think I would have gotten into programming if

it had been harder than that.

Why don't "real" programmers use tools that are as

straightforward as those employed by 10-year-olds?

Part of the reason VB could be so simple is because it

artificially constrained the problem space it could

address. You could probably only use the workflow I

described for Windows desktop applications. But if one

didn't care about integrating with other systems, that

was plenty. There was no need to call out to the network

or try to make your application work on different

devices.

Sunday, July 30

Watching videos on egghead.io about Redux. It looks

pretty exciting and I'm curious to see how they deal

with the problem of scaling a single state atom to a

large, complex application. It seems like you'd end up

with parts of the state that are only relevant for

particular views, and if you want that state to be

cleared out when a view is initialized (e.g. when the

app pops up a search modal, the search bar should start

out empty) it could get complicated or awkward to

manage. I guess you could have something akin to a

constructor/initializer for just that part of the state,

and use it to build the new state whenever that UI

component was initialized.

I'm also not sure what Redux really gains by forcing

the state atom to be immutable. App-level guarantees,

sure--maybe it's easier to write certain applications

when immutability is assured, but I'd prefer to leave it

up to the app developer to decide that. Since Redux can

in principle record every action that flows through a

reducer, and it knows the initial state of the app, it

could just play back actions on top of a known state

to implement "undo" functionality, time travel debug-

ging, or any of the other cool features that Redux

boasts. Recording actions instead of states seems like

it would have a more predictable memory footprint as

well. If you limit undo history to 1000 actions, you

have a pretty good idea of how much memory that will

use. If you're storing 1000 states, it's not at all

clear, since with structural sharing each action's

modification to the state could be tiny or a complete

rewrite.

Another thing I'm curious about is the possibility of

giving more expressive interfaces to the data atom.

What if (to give a basic example) you want an array in

your atom to act as a stack or queue, and be restricted

to stack/queue operations?

One possibility for this is to require each datastrucure

to expose fromJSON and toJSON methods that allow its

internal state to be persisted in the store. These

methods would be called by the OS to hydrate the state

before passing it to main().

Another example is the redux-data-structures package,

though this looks pretty redux-specific (the interface

to a data structure is not methods, but actions which

have predefined effects on the state).

[. . .]

Tuesday, August 1

DOOM AND GLOOM

THE HEAT DEATH OF CIVILIZATION

It should be obvious that a technologically advanced

civilization has more entropy (a higher number of

possible states) than a less advanced one. Part of this

is sheer population; part is the number of events (i.e.

communications) that can occur in the system.

Currently, we're observing that improved communication

technologies beget an exponential explosion of further

improvements, as barriers to collaboration and inform-

ation access are lowered.

I have to wonder, though: what's the end goal? A world

where everything happens all at once (a temporal singu-

larity)? A world where everyone is happy and prosperous

but no one understands why (too much info to process)?

We do things first and justify them later.

Why does everyone in tech have imposter syndrome? Could

it be that we all have no clue what we're doing? What's

more dangerous than a bunch of people with actual magic-

al powers pretending they know how to use them?

Dunning and Kruger, in their 1999 paper, stated that

competent people overestimate the abilities of others.

This could explain why imposter syndrome is so wide-

spread in tech. We're a society of competent people.

...and with that explanation, I've biased myself against

seeing any other. Great.

[. . .]

What is up with this editor? Why is it less frustrating

to edit code here than in Vim, which has *much* more

convenient navigation features?

In Vim, there are many ways to accomplish a given task.

Having to choose among these is a mental burden. Vim is

faster for many editing tasks, but for 99% of editing

all of those features just create mental drag even as

they speed you up. IDEs are no different.

When I have to go back and edit a line in Minmus, it's

annoying, but mindless. It doesn't really distract me

from whatever I was going to write next.

[. . .]

Thursday, August 3

Googled "Why is Redux state immutable" and came up with

issue 758 on the Redux github in which gaearon explains

that immutability allows an "aggressive"

shouldComponentUpdate method on Redux's React compon-

ents -- i.e. it compares pointers instead of walking the

object tree to determine equality. That makes sense, but

Grove apps have no components (the UI is modularized in

time instead of space!) and update() functions will

probably be able to signal via a null return that

nothing needs to be redrawn. Therefore, the concerns

about mutability that apply to Redux do not apply to

Grove apps.

Other arguments for immutability ("it makes programming

easier" or "it lets you get undo for free") are nonsense

because they're really arguments for a state atom, not

for immutability. The two concepts go together in most

frameworks so they're probably often confused.

ARE INTEGRATED TESTS STILL A SCAM?

When I was in Labs there were some die-hard holdovers

from the Rails 3 + Cucumber days who insisted that

every app must have comprehensive integrated tests.

"After all," they argued, "your whole job is to ship

software that performs a given function, and the only

way to verify that the software does that thing is to

run a test that actually does that thing". I disliked

this argument because it is correct. It is also very

inconvenient for me because I hate integrated tests.

Mostly, I hate them because they're slow, and because

the verification step rarely *looks* like the expected

output, so it's hard to know when a test fails if you

need to change the test or the code. At best, it's a red

flag that "something might be broken somewhere around

here" and then you need to start the app yourself and

manually check it out.

Gary Bernhardt states that the runtime of your integra-

ted test suite is superlinear in the size of your app

because each test you add grows the codepath that's

exercised by all the other tests. I think this is mostly

true for webapps because a) a lot of Rails apps have

a bunch of side effects (think model lifecycle hooks)

for every action, and b) the view is monolithic and

needs to be redrawn on every HTTP call, and it only gets

more complicated over time.

I don't think Grove apps' integration tests can suffer

from either of these problems. The state atom means that

updates are small and fast. The fact that views are

modularized in time means that there is no gargantuan

dashboard page that slows down every test. I don't

doubt that integrated tests will always get slightly

slower over time, but the increase is probably asymptot-

ic. Exponential growth seems unlikely.

The result of this is that Grove apps can probably lean

on integration tests to much greater effect than a

typical Rails app. Unit tests can then be used for the

units that are actually independent of the rest of the

app. No more mocks and stubs!

Grove apps' state atoms give you another big benefit:

test fixtures. You can generate one state with a

sequence of input commands, and then feed it in to

a bunch of other tests. This makes test setup extremely

fast: whereas each Rails integration test that uses

a logged-in user needs to run the authentication code,

in a Grove you can just reuse the state from the first

login over and over again (a silly example because

of course Grove apps don't need authentication!)

Sunday, November 12

After much hammocking, I think I have finally found a

solution to all the issues in the original Grove's high

level design.

In October, I gave a talk about Web Quines at Pivotal.

The idea for this talk was sparked by the realization

that it doesn't make a lot of sense for an offline

computing environment to be monolithic, even if there's

a unified platform behind it. If you don't want the

state of different apps to conflict, if you don't want

infinite loops or crashes in one app to affect the whole

system, if you want to easily find the version of your

system where you saved changes to some document, it

makes sense for each app to be its own, independently-

versioned thing. The version of this that I presented in

my talk is this: each app has its own HTML file that can

produce copies of itself. The copy-making genes are

shared by all these apps, uniting them into the family

of Web Quines. Their other DNA is unique, though.

Something still nagged, though. While web quines present

a close-to-optimal offline end-user experience, they

don't address the problems with software development

that I wanted to solve with the Grove project. Library

authoring and versioning is still a concern. Testing is

not seamless. The tools I developed to create Web Quines

use NodeJS and Jasmine. In order to satisfy my dream

of software development happening entirely in a browser,

I would need to build an IDE in a web quine.

Yesterday, I asked the question: why do apps need to run

outside the IDE? What if the way that end-users ran apps

was to load them into the IDE and just hit "run"?

If this sounds familiar, it's because it's how C64 Basic

worked. This approach has several advantages:

- Rather than being versioned with an IDE web quine, the

application code is in its own separate "floppy image"

along with all of the application's state. This makes

it easy to manually test the app and preserve state

across restarts. You can do some stuff in the app,

find a bug, tweak the code, and test again, and your

state will be preserved. Since the state files can

live in the same namespace as the code files, you have

a failsafe if your changes to code or state somehow

break the app: just go into the IDE and modify the

code and/or state.

- The size of the application files is minimal: each one

contains the code and state for just that application.

even libraries can be contained within the IDE.

- The IDE is stateless, so you only ever need to store

one copy of it.

- Since apps only run in the IDE, the IDE can provide

services that would be space-intensive to duplicate in

every app, like HTML DOM manipulation, fonts, and

graphics.

- In the first version of the Grove (the one you're

looking at now) I never really solved the problem of

how to distribute apps. The best I could come up with

was a) copy-pasting code into an "installer" file, or

b) cloning the entire system and emailing it to

someone, both of which have obvious UX flaws. Under

the new paradigm, you can send a single app image to

someone, including your save files (if you want) or

in a clean state (I assume most apps will have a

"factory reset" feature).

- Since libraries are bundled and versioned with the

IDE, concerns about compatibility and library upgrades

are minimized. End-users just need the version of the

IDE that was used to create the software in the first

place, and everything is guaranteed to work.

What about the problem that end-users won't understand

what an IDE is or why they should run apps from it?

Easy: just package the IDE to look like a physical

computer, and they'll get it.

Monday, November 13

I can use generator functions to create a REPL.

var code = ''

function *REPL() {

while(true) {

var res = eval(code)

console.log(res)

yield

}

}

var repl = REPL()

repl.next()

The 'yield' keyword will allow execution to return to

the caller of repl(). The caller can wait for input from

the user, and when it arrives, set `code` and then call

repl.next() again, which will resume where it left off.